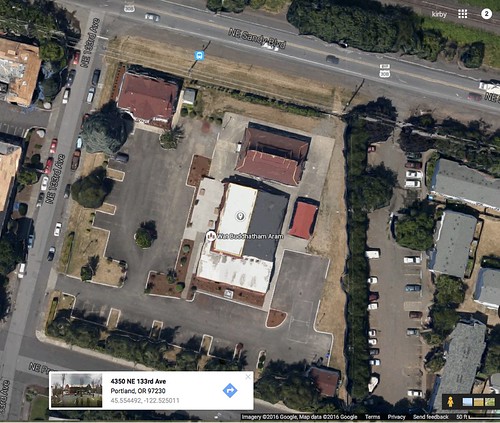

:: Wat Buddhatham Aram ::

This afternoon I attended a final presentation by Alan Potkin, during this April, 2016 trip to Portland, this time to elders of the Laotian community at a local Buddhist temple, on NE 133rd and Sandy. He'd presented to Wanderers at the Pauling House on Hawthorne, and to Thirsters on E Broadway, in the previous week.

I've driven by that temple campus many times, usually on my way to or from Costco, on NE 138th, but this was my first time to see the inside. Alan used a screen and computer projector, and we enjoyed amplified sound, both for his voice and the recorded video segments, including some in Lao.

A treat I'd not experienced before was Alan's head first dive into the epic Ramayana itself, while scrolling through the temple murals his team had helped to recreate.

The story (ພຣະລັກພຣະຣາມ) is known to some Laotians, and Wikipedia calls it the "national story", but it is perhaps not as core to the national storytelling as among some other Buddhist and Hindu nations, elsewhere in Asia? I'm no authority on these matters myself.

Alan had rescued another version he found tucked away in a cabinet of a forgotten old wat, forty three holy books in the khom language, which he's hoping to see translated into ordinary Lao. Only those schooled in the older traditions, such as monks and other scholars, can read khom.

When it comes to mega-projects, such as hydro-dams, or smaller, Dr. Potkin's message is pretty simple: making big changes to the landscape or seascape should entail making a detailed record of what it was like before the changes. Take inventory, be thorough. That's a best practice.

He does not automatically assume the more strident position of the most negatively impacted by such projects, that said developments must not occur. His position is more nuanced.

The trade-offs need to be addressed case by case, in light of clearly presented information, and if a project is to go ahead, then at the very least what the place was like before and after must be well-documented, using techniques used by museums and interpretive centers to communicate to the general public.

Keep updating the exhibits, about the Hanford cleanup for example (like OMSI had), with follow-up information, at intervals. Alan keeps checking back on the projects he tracks, so long as he's able, updating his document database. Outcomes research is also essential.

Turgid phone-book-sized reports are insufficient to get the info across, any museum curator could tell you that.

Given today's cyber-tools, a virtual museum is an affordable requirement, complete with oral histories, videos, and an inventory of flora and fauna and their migration patterns, and their roles in peoples lives. Alan thinks the Bonneville Power Administration made at least a decent attempt of building such an archive, before Celilo Falls went under, thanks to the Dalles dam.

One of Alan's favorite lessons revolves around a certain World Bank dam that was hastily retrofitted with a fish ladder that never worked, a last minute token attempt to compensate for the vast tonnage of edible protein that was about to be cut off, a fish migration cycle not fully appreciated.

The fish ladder never worked; it was built to the wrong scale for the migration in question. The dam is only able to produce about 40 megawatts of juice, and serves as an ongoing monument to the World Bank's ineptness, at least back then.

Have things improved? Look for those on-line museums of "before the project" exhibits, with detailed information about the local lifestyles, food sources, patterns of trade. If you don't find any such exhibits, assume the answer is no, it's business as usual.

I got through Costco for under $100, including the $1.50 hot dog + soda pop.