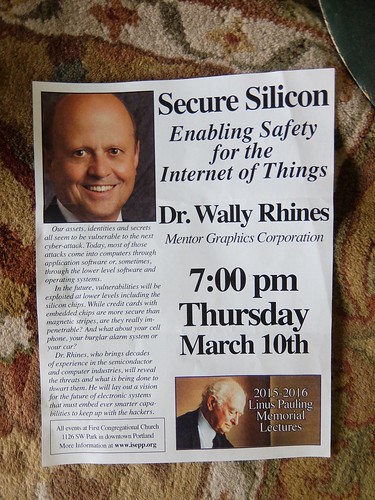

Wally Rhines is no mere bystander, and well beyond the engaged journalist, when it comes to understanding the risks to our security presented by this Internet of Things.

As the CEO of Mentor Graphics, Wally is at the helm of one of the few companies the makes the tools that make tools that make the chips those Things contain. Chips as in "micro-miniaturized circuit boards" designed to perform reliably and in a trustworthy manner.

What one industry sees as an embarrassing vulnerability, another will see as an exploitable hack.

The black hats challenge the white hats to do their jobs correctly, by breaking into their stuff in ways that should and could be prevented. The black hats are making a point: you need to stay on top of your game.

When only white hats abound, some will need to don black just to keep the skill sets up to snuff, the reflexes fresh, much as a human body will do when training to remember past insults. Memories get built.

Anti-virus software tends to be a huge database of signature byte strings.

Wally started his talk pointing out that humans owned an ever smaller percentage of IP numbers in that most of them belong not on "whois" people but "whatis" things (one could say).

You don't need to register as a "who" to be a toaster or refrigerator in somebody's household. IPv6 gives us plenty of addresses to spread Things around.

How are chips signed? Do we want them signed? What would the signature mean?

We're only beginning to answer these questions. CEOs yak about these topics a lot. Wally is on the road quite a bit, sharing these and other, more technical, slides.

The overall schema is an inverted pyramid in that the most widespread exploits involve various forms of social engineering, trickery around phishing and phoning in with false identities, milling about in smoking areas and befriending employees.

These kinds of security breaches may get wide publicity but affect fewer individuals than mega-downloads of supposedly confidential info. Sometimes social engineering leads to deeper exploits.

In one experiment, USB sticks were scattered in the parking lot, apparently dropped by mistake. How many finders-keepers types would insert these sticks in their own machines? Depressingly many.

Get yourself a quarantined box you're prepared to let fry, if you're wanting to do hobby forensics. Sure, random memory sticks might have interesting content but that doesn't mean accepting candy from strangers is suddenly a good idea.

Mass downloading exploits, as have been successfully conducted against Anthem Healthcare and the IRS (I've got files with both, so I'm a victim), may rely on security holes in the infrastructure itself, at the base of which are these all-important chips, signed and unsigned.

What if the chip itself is doing surveillance tasks supposedly for customer maintenance and satisfaction but with the side effect of providing a side door into private circuits? What if the chip itself is hackable? These kinds of vulnerability may be the hardest to find and yet affect the most people in the long run.

How might a customer verify that a purchased chip does just what the documentation says it does, and no more?

For example the Apple iPhone is currently vulnerable at least in principle but the Apple CEO is working overtime to close that gap.

Pretty soon, what the FBI is asking for will not be engineeringly feasible, whereas today one could enslave people to force the opening.

A safe is meant to be safe and many designs for software safes are in principle, mathematically, uncrackable, unless of course one gets very lucky with some wild guess, less likely than winning the lottery three times in a row.

Once the paper is out of the safe there's no guarantee it's still valuable. Securities are more vulnerable to shifting markets that crackable safes.

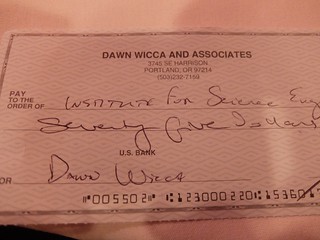

I took a ceremonial US Bank check from Dawn Wicca and Associates to commemorate Dawn's years as a bookkeeper for ISEPP, during a golden age. She died on St. Patrick's Day on 2007, and I'm thinking about her quite a bit.

Some of the donation was actually paying for a signed copy of Terry's new book, which I'm taking to Quaker Men's Group as worship-reading (also known as slow reading).

I was allowed to bring a guess and offered seats at the Heathman Dinner to a couple people, neither of whom could make it that night (Patrick joined me for the talk itself). I had a great time anyway.

Glenn has been working on his "elevator speech" for Global Matrix and tried it out on Wally, who's eye was drawn to the NSA crypto-analyst line towards the end.

Clearly Glenn was familiar with white and black hat territory.

I think I'd already left the scene by then, somewhat ironically sporting the black Stetson that Glenn gave me. I'd actually gone back to the car for it during Q&A, because I'd forgotten my bank check also. I moved the car closer to the venue.

Q&A was still going on when I got back. Wally was generous with his time. He appreciates these golden opportunities to engage the general public.

I'm more of a social engineering hacker than a hardware guy I'd say, and I'm more the kind to leave bread crumbs, make it a treasure hunt, like with geo-caching, perhaps with product placement worked in.

Sure, there are times I'd like to have been a fly on a wall, but I understand about authorized access and tend to steer clear of areas restricted against my kind.