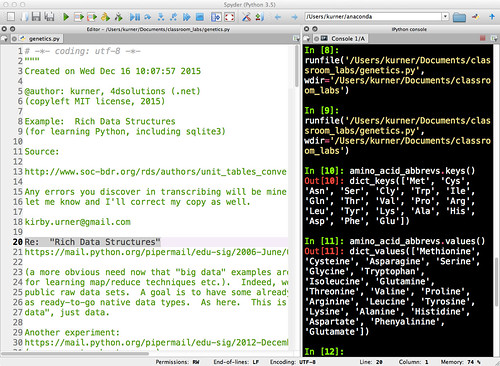

:: Python dicts mapping 64 DNA / RNA base pair triplets to 20 amino acids ::

The videos I'm watching on Safari On-line, about Hadoop, feature WordCount, a jarred job, working against a cluster containing all Shakespeare's writings in HDFS.

To unpack that a little, making a cluster of computers act in concert as a very large hard-drive, with RAID-like redundancy, is what cloud computing is all about.

You can build a cloud in your basement if you want to invest in the hardware. You'll want two robust carrier grade master servers: one for NameNode and JobTracker, the other for Secondary NameNode (the change-log compactor, not meant to be considered a failover).

The six to one hundred slaves (for starters) may use commodity hardware. One DataNode per slave machine keeps things easy, with paired TaskTracker too, each of these five types of daemon a long-running process on its own JVM.

This entire ensemble acts to emulate a giant disk, and actually the texts attributed to Shakespeare don't even begin to take up that kind of room. The redundancy factor provides a high degree of security, provided the cluster is actively monitored and maintained, failed hardware replaced.

And by "a jarred job" I meant "stored in a jar file" (like a zip file or tarball), as we talk to this cluster in terms of these Java language jobs. An ecosystem of software products, including open source, defines the Hadoop namespace more or less. Sqoop, Hive, Pig... a bunch of funny names.

A map routine, farmed out to work against data blocks simultaneously, harvests the data for the reducers, which apply whatever amalgamating logic, summing columns, counting rows, number crunching against whatever the mappers have found.

That's all technology for dealing with Big Data.

At the other end of the spectrum, we have tiny data sets that are nevertheless more substantive than random semi-spurious examples. In the age of print, squandering pages on "real data" (such as a complete Periodic Table of the Elements) would not be undertaken lightly. The Periodic Table is concise for a reason.

How many "parts in inventory" does one need to get the idea? Of parts, not that many, but "many" is a concept to get one's head around also. An appreciation for the sheer volume of the data being managed may be illuminating as well (in the sense of instructive).

Once in a real knowledge domain, the data often starts getting bigger, even if the business logic remains more or less constant over time. The same rules come to apply to more and more special cases -- not that rules never change.

Fortunately, and just in time when we needed it most, we often now get to learn new skills by downloading substantive example files, as it's not a matter of "wasting paper" like in the old days. The move towards Open Data is a way to balance higher rates of collection. Enriching the commons with more shared data provides more reality checks which presumably better guides public policy.

Having substantive files, such as William Shakespeare's works, or even just tiny maps of the genetic code, also helps us keep the bandwidth high. You're not just learning some computer language, you're being reminded of what you learned about genetics.

Sharing bread and butter data from different disciplines, not phony nonsense examples, helps keep a subject matter grounded, and gives people more windows into one another's spheres of concern.

Yes, I understand the utility of "meaningless story problems" designed to call attention to what's most generalizable, the core concepts and techniques. By the same token, peppering one's teaching with real-world-flavored examples has valid uses as well. It's not either / or.