I've got my nose back in Luciano Ramalho's Fluent Python this morning, in Safari On-line. I caught two of Luciano's talks at OSCON this year, and have downloaded their recorded versions. The book itself has been a bestseller in its category on Amazon.

I've always want to see a concise Pythonic narrative that ties back to underlying C code and here I'm finding that. For example Luciano does a great job describing the hash table algorithm behind dicts and sets, and then links directly to source code, where we find these comments:

The basic lookup function used by all operations.

This is based on Algorithm D from Knuth Vol. 3, Sec. 6.4.

Open addressing is preferred over chaining since the link overhead for

chaining would be substantial (100% with typical malloc overhead).

The initial probe index is computed as hash mod the table size. Subsequent

probe indices are computed as explained earlier.

All arithmetic on hash should ignore overflow.

The details in this version are due to Tim Peters, building on many past

contributions by Reimer Behrends, Jyrki Alakuijala, Vladimir Marangozov and

Christian Tismer.

Having a link directly to Knuth's The Art of Computer Programming in the comments for the Python dict object grounds a specific source code implementation in the computer science behind it. Great for digital mathematics teachers in need of heuristics.I have that Knuth volume upstairs. What a great way to learn. Plus I have the Python REPL (pronounced "reh-pull") open in another window.

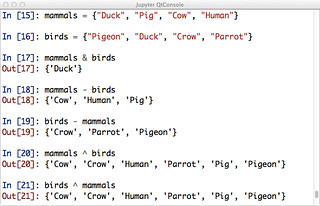

In going over the set data structure and its operations, I was thinking back to New Math and elementary school, when set notation was making its early entry into kid consciousness. This was unfamiliar material to most teachers and much of it was junked in the ensuing backlash. But we had no REPL back then (a few lucky college kids had ISETL maybe?), what if we'd had one?

But in 2015, why not boot a Python interpreter at some point when typing has been mastered? Learn about union, complement, difference, intersection all over again. It's just like New Math, but with more machinery to back it up. I call it Gnu Math.

Speaking of typing, my friend Glenn reminded me why he can't type effectively, even after a lifetime as a typist: most keyboards don't allow resting fingers on keys whereas in his time with NSA he had to pound through ten-ply fan-fold. When he tries to type on a keyboard, he floods his own text with errors. So frustrating!

Maybe there's some steampunk solution where an old mechanical Royal typewrite type keyboard is wired up as a USB peripheral? My retired college professor friend Chuck Bolton never seemed to master the new keyboard either. The Royal sits proudly in the living room.

In sharing Python with art history students or journalists, what's more important than exhaustive practice or keyboarding is an appreciation for the layers of culture, the ecosystem. How does C source code relate to Python and what's a hash table? That's enough of a story for one article.

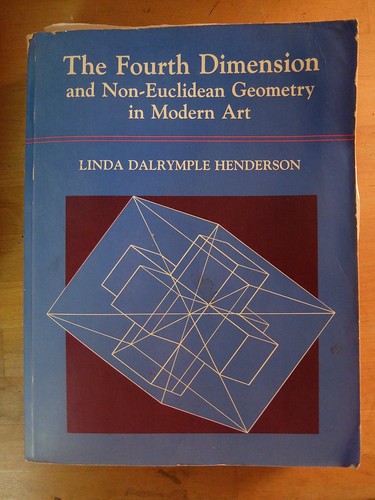

Why I'm addressing art historians these days has to do with the '4D meme' in the art world since the late 1800s, the core topic of another book I sometimes reread and review: Linda Dalrymple Henderson's The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art.

Through Python, I introduce art history students to the topic of Quadrays or Q-rays, needing no more than some high school XYZ mathematics, thereby helping to anchor the '4D' meme as Fuller used it. I also introduce Q-rays in Martian Math a curriculum field tested with high and middle school students at the Reed College and Portland University campuses.