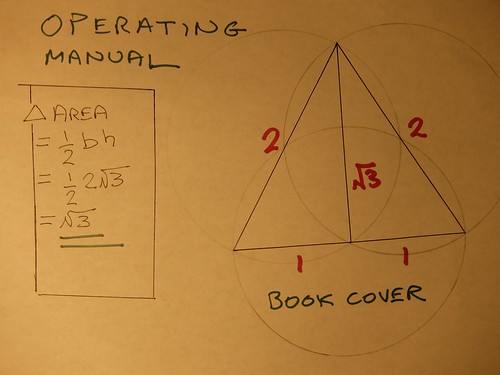

I was reminiscing with David Koski recently, about the "operating manual" he placed flat open on the table, triangular book covers, just the one page. The edges of the book covers, including hinge, are all two, the diameter of a unit sphere.

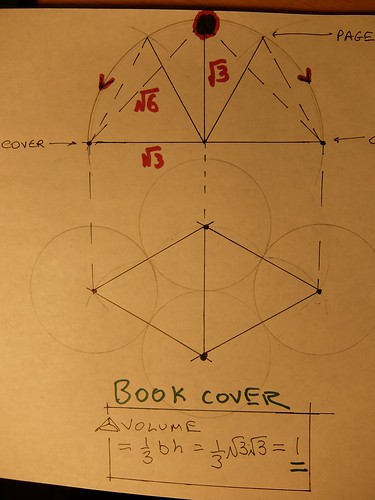

Imagine a page swinging back and forth, wagging, a triangle just as big as both book covers. It has an eye hook at the apex, something for taut string to pass through, should we want to emphasize this sixth edge of the two tetrahedrons. Yes the "page" can stay stiff. This is a moving sculpture I'm describing.

The two tetrahedrons have this page as their wall-in-common. As the page wags back and forth, two neighboring tetrahedrons co-vary and thanks to "base times height" have equal volume. One may be a regular tetrahedron, with the other more a wedge, yet they'll both have the same volume, whatever we set that to be.

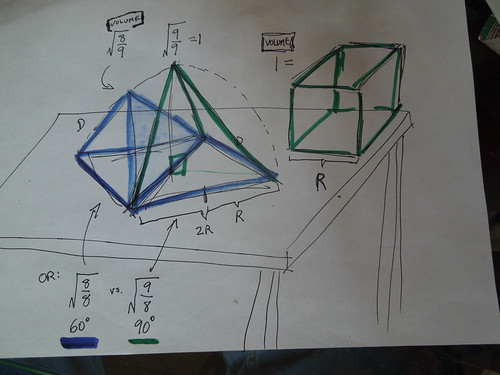

Imagine holding three ping pong balls in a triangle, a fourth one in the valley between. That's a starting place. Now take one of those balls (of radius R, diameter D) and pivot it around any two-ball valley to assume an angle of 90 degrees to the no-longer-touching furthest ball. That's √6, ball center to ball center (longer than 2 for sure).

The equilateral triangle of edges 2, both page and two book covers, has a vertical mid-edge to opposite vertex altitude of √3. The Pythagorean Theorem hasn't changed.

The right triangles defining each book cover have legs 1, √3, and hypotenuse 2. Area? Base times height over two = 2 * √3/2 = √3 per each book cover.

So what's the volume of each right tetrahedron defined by the single page pointing straight upward, at 90 degrees to the book covers open flat? The string from each book cover apex, to the eye hook in the page, is √6.

Even without that fact, however, we have the base, √3, and we have the height, also √3. Multiply those together and divide by three, per volume of tetrahedron formula, and we have 1. Exactly.

Having achieved a volume of one, lets switch to a corresponding cube of edges R, with R being the radius of diameter D spheres. Our original tetrahedron, recall, started with four of those. Then we spread a pair further apart. Anyway, our cube of edges R has a volume identical to each of the two right tetrahedrons just described.

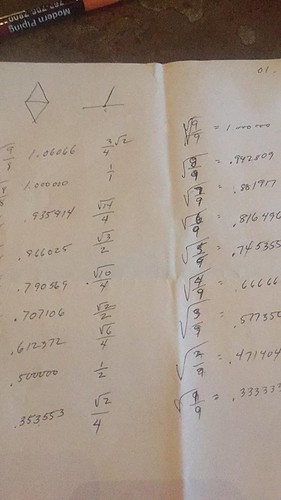

What do we do with this fact? The starting tetrahedron of four closest packed ping pong balls was where we start when measuring volume in our Synergetics namespace, perhaps branded as Martian Math in your neighborhood.

The right tetrahedrons associated with the vertical page each have a larger volume, by a factor of the √(9/8), about 1.06. We may want to use this constant when switching back and forth between two volumetric evaluations of the same vista, in doing unit conversion.

Imagine a page swinging back and forth, wagging, a triangle just as big as both book covers. It has an eye hook at the apex, something for taut string to pass through, should we want to emphasize this sixth edge of the two tetrahedrons. Yes the "page" can stay stiff. This is a moving sculpture I'm describing.

The two tetrahedrons have this page as their wall-in-common. As the page wags back and forth, two neighboring tetrahedrons co-vary and thanks to "base times height" have equal volume. One may be a regular tetrahedron, with the other more a wedge, yet they'll both have the same volume, whatever we set that to be.

Imagine holding three ping pong balls in a triangle, a fourth one in the valley between. That's a starting place. Now take one of those balls (of radius R, diameter D) and pivot it around any two-ball valley to assume an angle of 90 degrees to the no-longer-touching furthest ball. That's √6, ball center to ball center (longer than 2 for sure).

The equilateral triangle of edges 2, both page and two book covers, has a vertical mid-edge to opposite vertex altitude of √3. The Pythagorean Theorem hasn't changed.

The right triangles defining each book cover have legs 1, √3, and hypotenuse 2. Area? Base times height over two = 2 * √3/2 = √3 per each book cover.

So what's the volume of each right tetrahedron defined by the single page pointing straight upward, at 90 degrees to the book covers open flat? The string from each book cover apex, to the eye hook in the page, is √6.

Even without that fact, however, we have the base, √3, and we have the height, also √3. Multiply those together and divide by three, per volume of tetrahedron formula, and we have 1. Exactly.

Having achieved a volume of one, lets switch to a corresponding cube of edges R, with R being the radius of diameter D spheres. Our original tetrahedron, recall, started with four of those. Then we spread a pair further apart. Anyway, our cube of edges R has a volume identical to each of the two right tetrahedrons just described.

What do we do with this fact? The starting tetrahedron of four closest packed ping pong balls was where we start when measuring volume in our Synergetics namespace, perhaps branded as Martian Math in your neighborhood.

The right tetrahedrons associated with the vertical page each have a larger volume, by a factor of the √(9/8), about 1.06. We may want to use this constant when switching back and forth between two volumetric evaluations of the same vista, in doing unit conversion.